See plus plus :) .

0. Notes

printf/snprintf Cheat Sheet {C / C++}

Integer

| Data type | Specifier | Notes |

|---|---|---|

int8_t / signed char |

%hhd |

signed 8-bit |

uint8_t / unsigned char |

%hhu |

unsigned 8-bit |

int16_t / short |

%hd |

signed 16-bit |

uint16_t / unsigned short |

%hu |

unsigned 16-bit |

int32_t / long |

%ld |

signed 32-bit |

uint32_t / unsigned long |

%lu |

unsigned 32-bit |

int64_t / long long |

%lld |

signed 64-bit |

uint64_t / unsigned long long |

%llu |

unsigned 64-bit |

Floating point

| Data type | Specifier | Notes |

|---|---|---|

float |

%f |

4-byte float |

double |

%f |

Arduino AVR: double = float |

long double |

%Lf |

depends on platform |

%e→ scientific notation%g→ auto select%for%e

Char / String

| Data type | Specifier | Notes |

|---|---|---|

char |

%c |

single character |

char* / String |

%s |

null-terminated string |

Pointer / Address

| Data type | Specifier | Notes |

|---|---|---|

void* |

%p |

memory address, hex |

Hex / Octal / Binary

| Data type | Specifier | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| unsigned int | %x / %X |

hexadecimal |

| unsigned int | %o |

octal |

| Arduino only | %b |

binary |

Flags, Width, Precision

%-10d→ left-justify, width 10%010d→ pad with zeros, width 10%.2f→ 2 decimal digits%*d→ dynamic width

Specific Notes

uint32_t→%luint32_t→%lduint16_t→%uint16_t→%dor%hduint8_t→%uor%hhuint8_t→%dor%hhdfloat→%f- Use

snprintf()with correctly sized buffer to avoid overflow

Code Timming

- C++11 comes with some functionality in the chrono library to time our code to see how long it takes to run.

- e.g.

#include <array>

#include <chrono> // for std::chrono functions

#include <cstddef> // for std::size_t

#include <iostream>

#include <numeric> // for std::iota

const int g_arrayElements { 10000 };

class Timer

{

private:

// Type aliases to make accessing nested type easier

using Clock = std::chrono::steady_clock;

using Second = std::chrono::duration<double, std::ratio<1> >;

std::chrono::time_point<Clock> m_beg{ Clock::now() };

public:

void reset()

{

m_beg = Clock::now();

}

double elapsed() const

{

return std::chrono::duration_cast<Second>(Clock::now() - m_beg).count();

}

};

void sortArray(std::array<int, g_arrayElements>& array)

{

// Step through each element of the array

// (except the last one, which will already be sorted by the time we get there)

for (std::size_t startIndex{ 0 }; startIndex < (g_arrayElements - 1); ++startIndex)

{

// smallestIndex is the index of the smallest element we’ve encountered this iteration

// Start by assuming the smallest element is the first element of this iteration

std::size_t smallestIndex{ startIndex };

// Then look for a smaller element in the rest of the array

for (std::size_t currentIndex{ startIndex + 1 }; currentIndex < g_arrayElements; ++currentIndex)

{

// If we've found an element that is smaller than our previously found smallest

if (array[currentIndex] < array[smallestIndex])

{

// then keep track of it

smallestIndex = currentIndex;

}

}

// smallestIndex is now the smallest element in the remaining array

// swap our start element with our smallest element (this sorts it into the correct place)

std::swap(array[startIndex], array[smallestIndex]);

}

}

int main()

{

std::array<int, g_arrayElements> array;

std::iota(array.rbegin(), array.rend(), 1); // fill the array with values 10000 to 1

Timer t;

sortArray(array);

std::cout << "Time taken: " << t.elapsed() << " seconds\n";

return 0;

}

Command line

- Command line arguments are optional string arguments that are passed by the operating system to the program when it launch.

- Passing command line arguments: we simply list the command line arguments right after the executeable name.

- Using command line arguments: by using different form of main():

main(int argc, char* argv[])/main(int argc, char** argv)argc: argument count, always be at least 1, because the first argument is always the name of the program itself.argv: is where the actual argument values are stored (think: argv = argument values)

- e.g.

#include <iostream>

#include <sstream> // for std::stringstream

#include <string>

int main(int argc, char* argv[])

{

if (argc <= 1)

{

// On some operating systems, argv[0] can end up as an empty string instead of the program's name.

// We'll conditionalize our response on whether argv[0] is empty or not.

if (argv[0])

std::cout << "Usage: " << argv[0] << " <number>" << '\n';

else

std::cout << "Usage: <program name> <number>" << '\n';

return 1;

}

std::stringstream convert{ argv[1] }; // set up a stringstream variable named convert, initialized with the input from argv[1]

int myint{};

if (!(convert >> myint)) // do the conversion

myint = 0; // if conversion fails, set myint to a default value

std::cout << "Got integer: " << myint << '\n';

return 0;

}

- Things that can impact the performance of the program: TBD

- Measuring performance:

- gather at least 3 results.

- the program runs in 10 seconds etc

1. Introduction

- C++ was developed as an extension to C. It adds man few features to the C language, and tis perhaps best through of as a superset of C.

Step 1: Define the problem that you would like to solve

- I want to write a program that will …

Step 2: Determine how you are going to solve the problem Determine how we are going to solve the problem you came up with in step 1.

- They are straightforward (not overly complicated or confusing).

Step 3: Write the program

#include <iostream>

int main()

{

std::cout << "Here is some text.";

return 0;

}

Step 4: Compiling your source code

- We use a C++ compiler: MinGW/GCC, Clang, … for many different OS.

- The C++ compiler sequentially goes through each source code file and does two important tasks:

- checks your C++ code to make sure it follows the rules of the C++ language.

- translates your C++ code into machine language instructions. These instructions are stored in an intermediate file called an object file.

Step 5: Linking object files and libraries

- After the compiler has successfully finished, another program called the linker kicks in: ar,ld, …

- Linking is to combine all the object files and produce the desired output file (.exe, .elf, .hex ..)

NOTE: Building refer to the full process of converting source code files into an executable that can be run. For complex project, build automation tools such as make, cmake are often used.

Steps 6 & 7: Testing and Debugging

2. Setup Environment, IDE (Integrated Development Environment):

-

We need to installing IDE or st that comes with a compiler that supports at least C++17: GCC/G++7, Clang++ 8,…

-

Some of the options typically does:

- Build: compiles all modified code files in the project or workspace/solution, and then links the object files into an executable. If no code files have been modified since the last build, this option does nothing.

- Clean: removes all cached objects and executables so the next time the project is built, all files will be recompiled and a new executable produced.

- Rebuild: does a “clean”, followed by a “build”.

- Compile: recompiles a single code file (regardless of whether it has been cached previously). This option does not invoke the linker or produce an executable.

- Run/start: executes the executable from a prior build. Some IDEs (e.g. Visual Studio) will invoke a “build” before doing a “run” to ensure you are running the latest version of your code. Otherwise (e.g. Code::Blocks) will just execute the prior executable.

-

Examples:

- Create main.c

#include <iostream>

#include <limits>

int main(){

std::cout << "Hello world";

std::cin.get(); // get one more char from the user

return 0;

}

- Run following commands

Microsoft Windows [Version 10.0.19045.5371]

(c) Microsoft Corporation. All rights reserved.

C:\Users\phong.nguyen-van\Desktop\datasets\github\Cpp\example1>ls

main.cpp

C:\Users\phong.nguyen-van\Desktop\datasets\github\Cpp\example1>g++ --version

g++ (MinGW.org GCC-6.3.0-1) 6.3.0

Copyright (C) 2016 Free Software Foundation, Inc.

This is free software; see the source for copying conditions. There is NO

warranty; not even for MERCHANTABILITY or FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE.

C:\Users\phong.nguyen-van\Desktop\datasets\github\Cpp\example1>g++ main.cpp -o main.o

C:\Users\phong.nguyen-van\Desktop\datasets\github\Cpp\example1>g++ main.o -o main.exe

C:\Users\phong.nguyen-van\Desktop\datasets\github\Cpp\example1>main.exe

Hello world

3. Configuring the compiler

3.1. Build configurations:

- It is a collection of project settings that determines how the project will be built.

- Debug configurations: for debugging, turns off all optimizations, larger and slow, but ease

- Release configurations: for releasing, optimized for size and performance.

- For gcc/clang, the

-0#option is used to control optimize settings.

3.2. Compiler extensions:

- Many compilers implement their own changes to the language, often to enhance compatibility with other versions of the language

- For gcc/clang, the

-pedantic-errorsoption is used to disable the compiler extension.

3.3. Warning/Error level

- When compile the program, the compiler will check the rules of languages/compiler extension, and emit diagnostic messages.

- For gcc users: the

-Wall -Weffc++ -Wextra -Wconversion -Wsign-conversionoptions is used to enable the warning levels.

3.4. Language standard

C++98, C++03, C++11, C++14, C++17, C++20, C++23,...- For gcc/g++/clang, the

-std=c++17option is used to set the language standard.

4. C++ Basic

Data: informationValue: piece of dataObject: store a value in memoryVariable: an object has a name(identifier)Initialization: provides an initial value for a variable.

4.1. Initialization

// 1. default

int a;

// 2. traditional

int b = 5; // copy-initialization

int c (6); // direct-initialization

// 3. Modern

int d{7};

int e{};

{}vs():

int a{3.14}; // Compile ERROR

int b = 3.14; // Compile OK but b = 3

int x{}; // = 0

int y; // garbage value

copy initializationvsdirect initialization

struct Foo {

Foo(int) {}

explicit Foo(double) {}

};

Foo f1 = 5; // OK copy init → calls Foo(int)

Foo f2(5); // OK direct init → calls Foo(int)

Foo f3 = 3.14; // ERROR (explicit ctor not allowed here)

Foo f4(3.14); // OK direct init works with explicit → calls Foo(double)

4.2. iostream

std::cin >> x: console input to xstd::cout << x: console output\nvsstd::endl:\n: newline (fast, no flush)std::endl: newline + flush output buffer (slower)

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

int main() {

int x;

// input

cout << "Enter a number: ";

cin >> x; // std::cin >> x → console input

// output

cout << "You entered: " << x << '\n'; // \n → newline only

cout << "You entered again: " << x << endl; // endl → newline + flush

return 0;

}

4.3. Keywords and identifiers

-

Keywords: alignas alignof and and_eq asm auto bitand bitor bool break case catch char char8_t (since C++20) char16_t char32_t class compl concept (since C++20) const consteval (since C++20) constexpr constinit (since C++20) const_cast continue co_await (since C++20) co_return (since C++20) co_yield (since C++20) decltype default delete do double dynamic_cast else enum explicit export extern false float for friend goto if inline int long mutable namespace new noexcept not not_eq nullptr operator or or_eq private protected public register reinterpret_cast requires (since C++20) return short signed sizeof static static_assert static_cast struct switch template this thread_local throw true try typedef typeid typename union unsigned using virtual void volatile wchar_t while xor xor_eq

-

Identifiers:

snake_casevscamelCase

When working in an existing program, use the conventions of that program. Use modern best practices when writing new programs.

4.4. Literals vs Operators

Literals: fixed values like 42, 3.14, ‘A’, “Hello”, true, nullptr.Operators: symbols that act on values (+ - * / %, == != < >, && || !, = += -=, etc.).

4.5. Expression

- An expression is anything that produces a value when compilling.

Khai báo: tên biến chỉ là identifier (chưa phải expression). Sử dụng: tên biến trở thành một expression

5 + 3 // expression → evaluates to 8

x * y - 2 // expression → depends on x, y

func(10) // function call expression

true && flag // logical expression

5. C++ Basic: Functions and Files

5.1. Function

- Syntax:

returnType functionName(); // forward declaration

.....

returnType functionName() // This is the function header (tells the compiler about the existence of the function)

{

// This is the function body (tells the compiler what the function does)

}

- A

forward declarationallows us to tell the compiler about the existence of an identifier before actually defining the identifier. We have to be explicit about the return type. - e.g.

#include <iostream>

#include <type_traits> // for std::common_type_t

// Forward declare

template <typename T, typename U>

auto max(T x, U y) -> std::common_type_t<T, U>; // returns the common type of T and U

int main()

{

std::cout << max(2, 3.5) << '\n';

return 0;

}

// Definition

template <typename T, typename U>

auto max(T x, U y) -> std::common_type_t<T, U>

{

return (x < y) ? y : x;

}

5.2. name space

namespaceis a way to group names (variables, functions, classes) together and avoid name conflicts. It guarantees that all identifiers within the namespace are unique

// Issue

int value = 10;

int main() {

int value = 20; // conflict with global value

return 0;

}

// Solution

namespace Config {

int value = 10;

}

int main() {

int value = 20;

std::cout << value << " " << Config::value;

}

using namespace: this is a using-directive that allows us to access names in the std namespace with no namespace prefix- define namespaces and use the scope resolution operator (::) to access.

- the scope resolution operator can also be used in front of an identifier without providing a namespace name.

- namespaces can be nested inside other namespaces.

- we can create namespace aliases, which allow us to temporarily shorten a long sequence of namespaces into something shorter.

void doSomething() // this print() lives in the global namespace

{

std::cout << " there\n";

}

namespace Foo // define a namespace named Foo

{

// This doSomething() belongs to namespace Foo

int doSomething(int x, int y)

{

return x + y;

}

}

int main()

{

std::cout << Foo::doSomething(4, 3) << '\n'; // use the doSomething() that exists in namespace Foo

std::cout << ::doSomething(4, 3) << '\n'; // use the global doSomething()

namespace Active = Foo::Goo; // active now refers to Foo::Goo

return 0;

}

5.3. Preprocessor

- The preprocessor is a process that runs on the code before it is compiled.

#include <iostream> // insert file contents

#define NAME "Alex" // replace NAME → "Alex"

#ifdef NAME_DEFINED // only compile if defined

std::cout << NAME;

#endif

5.4. Header files

- Header files are files designed to propagate declarations to code files.

- Include header files:

#include <iostream>

#include "my_header.h"

"" → search local first, then system

<> → search system only

- Include header files from other directories: using

g++ -o main -I./source/includes -I/home/abc/moreHeaders main.cpp

// Issue: hard-coding long/absolute paths in #include

#include "headers/myHeader.h"

#include "/home/abc/moreHeaders/myOtherHeader.h"

// Solution: add include directories with -I

g++ -o main -I./source/includes -I/home/abc/moreHeaders main.cpp

#include "myHeader.h"

#include "myOtherHeader.h"

5.5. Header guard

- Header guards prevent the contents of a header from being included more than once into a given code file.

- For cross-platform library code,

#ifndefis safest. - For modern projects using GCC/Clang/MSVC,

#pragma onceis simpler and safe.

5.6. Others

https://www.learncpp.com/cpp-tutorial/how-to-design-your-first-programs/

6. Debugging C++ Programs

7. Fundamental Data Types

- Memory can only store bits. Data type help compiler and CPU take care of encoding the value into the sequence of bits.

- Fundamental Data Types Compound Data Types

7.1. Basic datatype (Primitive type)

| Types | Category | Meaning | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| float, double, long double | Floating Point | a number with a fractional part | 3.14159 |

| bool | Integral (Boolean) | true or false | true |

| char, wchar_t, char8_t (C++20), char16_t (C++11), char32_t (C++11) | Integral (Character) | a single character of text | ‘c’ |

| short int, int, long int, long long int (C++11) | Integral (Integer) | positive and negative whole numbers, including 0 | 64 |

| std::nullptr_t (C++11) | Null Pointer | a null pointer | nullptr |

| void | Void | no type | n/a |

7.2. Sizeof

- We can use

sizeofcan be used to return thesize of a type in bytes.

| Category | Type | Minimum Size | Typical Size |

|---|---|---|---|

| Boolean | bool | 1 byte | 1 byte |

| Character | char | 1 byte (exactly) | 1 byte |

| Character | wchar_t | 1 byte | 2 or 4 bytes |

| Character | char8_t | 1 byte | 1 byte |

| Character | char16_t | 2 bytes | 2 bytes |

| Character | char32_t | 4 bytes | 4 bytes |

| Integral | short | 2 bytes | 2 bytes |

| Integral | int | 2 bytes | 4 bytes |

| Integral | long | 4 bytes | 4 or 8 bytes |

| Integral | long long | 8 bytes | 8 bytes |

| Floating point | float | 4 bytes | 4 bytes |

| Floating point | double | 8 bytes | 8 bytes |

| Floating point | long double | 8 bytes | 8, 12, or 16 bytes |

| Pointer | std::nullptr_t | 4 bytes | 4 or 8 bytes |

7.3. Signed/ Unsigned

- a signed integer can hold both positive and negative numbers (and 0).

- Unsigned integers are integers that can only hold non-negative whole numbers.

7.4. Fixed-width integers and size_t

fixed-width integers: C++11 provides an alternate set of integer types that are guaranteed to be the same size on any architecture

#include <cstdint>

// Fixed-width integer types

std::int8_t i8; // 1 byte signed range: -128 to 127

std::uint8_t u8; // 1 byte unsigned range: 0 to 255

std::int16_t i16; // 2 bytes signed range: -32,768 to 32,767

std::uint16_t u16; // 2 bytes unsigned range: 0 to 65,535

std::int32_t i32; // 4 bytes signed range: -2,147,483,648 to 2,147,483,647

std::uint32_t u32; // 4 bytes unsigned range: 0 to 4,294,967,295

std::int64_t i64; // 8 bytes signed range: -9,223,372,036,854,775,808

// to 9,223,372,036,854,775,807

std::uint64_t u64; // 8 bytes unsigned range: 0 to 18,446,744,073,709,551,615

fast integers: guarantee at least # bits, but pick the type that the CPU can process fastest (even if it uses more memory).least integers: guarantee at least # bits, but pick the type that uses the least memory (even if it’s slower).

#include <cstdint> // for fast and least types

#include <iostream>

int main()

{

std::cout << "least 8: " << sizeof(std::int_least8_t) * 8 << " bits\n";

std::cout << "least 16: " << sizeof(std::int_least16_t) * 8 << " bits\n";

std::cout << "least 32: " << sizeof(std::int_least32_t) * 8 << " bits\n";

std::cout << '\n';

std::cout << "fast 8: " << sizeof(std::int_fast8_t) * 8 << " bits\n";

std::cout << "fast 16: " << sizeof(std::int_fast16_t) * 8 << " bits\n";

std::cout << "fast 32: " << sizeof(std::int_fast32_t) * 8 << " bits\n";

return 0;

}

7.5. std::size_t

- The type returned by the

sizeof. - size_t is an unsigned integral type that is used to represent the size or length of objects.

#include <cstddef> // for std::size_t

#include <iostream>

int main()

{

std::cout << sizeof(std::size_t) << '\n';

return 0;

}

7.6. Scientific notation

e/E: to represent the “times 10 to the power of” part of the equation. (e.g. 5.9722 x 10²⁴ -> 5.9722e24)

7.7. Floating point number

-

std::couthas a default precision of 6 -

We can override the default precision that std::cout shows by using an output manipulator function named

std::setprecision() -

fsuffix means float -

rounding error: cannot be represented exactly in binary floating-point, so printing with high precision reveals a tiny rounding error.

#include <iomanip> // for std::setprecision()

#include <iostream>

int main()

{

double d{0.1};

std::cout << d << '\n'; // use default cout precision of 6 -> 0.1

std::cout << std::setprecision(17); // -> 0.10000000000000001

std::cout << d << '\n';

return 0;

}

Inf: which represents infinity. Inf is signed, and can be positive (+Inf) or negative (-Inf). (5/0)NaN: which stands for “Not a Number”. (mathematically invalid)

7.8. Boolean values

std::boolalpha: use to print true or false (and allow std::cin to accept the words false and true as inputs)

7.9. Chars

- The integer stored by a

charvariable are intepreted as anASCII character. std::cin.get()this function does not ignore leading whitespaceEscape sequences:

| Name | Symbol | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Alert | \a |

Makes an alert, such as a beep |

| Backspace | \b |

Moves the cursor back one space |

| Formfeed | \f |

Moves the cursor to next logical page |

| Newline | \n |

Moves cursor to next line |

| Carriage return | \r |

Moves cursor to beginning of line |

| Horizontal tab | \t |

Prints a horizontal tab |

| Vertical tab | \v |

Prints a vertical tab |

| Single quote | \' |

Prints a single quote |

| Double quote | \" |

Prints a double quote |

| Backslash | \\ |

Prints a backslash |

| Question mark | \? |

Prints a question mark (no longer relevant) |

| Octal number | \{number} |

Translates into char represented by octal |

| Hex number | \x{number} |

Translates into char represented by hex number |

't': Text between single quotes is treated as a char literal, which represents a single character."text": Text between double quotes (e.g. “Hello, world!”) is treated as a C-style string literal, which can contain multiple characters.

7.10. Type conversion

implicit type conversion: e.g.double d { 5 };// okay: int to double is safeexplicit type conversion:static_cast<new_type>(expression)

8. Constant

- A constant is a value that may not be changed during the program’s execution. C++ supports two types of constants: named constants, and literals.

- Named constants are constant values that are associated with an identifier. Included:

- Constant variables

- Macros with substitution text

- Enumerated constant

- Literal are constant values that are not associated with an identifier.Literals are values that are inserted directly into the code.

8.1. Named constants

// Const variable

const double gravity { 9.8 };

// Object-like macros with substitution text

#define MY_NAME "Phong"

// Enumerated constant

As of C++23, C++ only has two type qualifiers: const and volatile. The volatile qualifier is used to tell the compiler that an object may have its value changed at any time. This rarely-used qualifier disables certain types of optimizations.

8.2. Literals

- Literals are values that are inserted directly into the code.

- Type of a literal is deduced from the literal’s value.

return 5; // 5 is an integer literal -> type: int

bool myNameIsAlex { true }; // true is a boolean literal -> type: bool

double d { 3.4 }; // 3.4 is a double literal -> type: double

std::cout << "Hello, world!"; // "Hello, world!" is a C-style string literal -> type: const char[14]

- Literal suffixes used to explicitly declare the type for a literal.

#include <iostream>

int main()

{

std::cout << 5.0 << '\n'; // 5.0 (no suffix) is type double (by default)

std::cout << 5.0f << '\n'; // 5.0f is type float

return 0;

}

8.3. Numeral systems (decimal, binary, hexadecimal, and octal)

- Numeral system literals in C++:

- Decimal (no prefix, 42)

- Binary (0b101010)

b - Hexadecimal (0x2A)

x - Octal (052) — all represent the same value.

#include <iostream>

int main()

{

int bin{}; // assume 16-bit ints

bin = 0x0001; // assign binary 0000 0000 0000 0001 to the variable

bin = 0b1; // assign binary 0000 0000 0000 0001 to the variable

bin = 0b11; // assign binary 0000 0000 0000 0011 to the variable

std::cout << std::bitset<4>{ 0b1010 } << '\n'; // create a temporary std::bitset and print it

// - C++14 also adds the ability to use a quotation mark (‘) as a digit separator.

int bin { 0b1011'0010 }; // assign binary 1011 0010 to the variable

long value { 2'132'673'462 }; // much easier to read than 2132673462

return 0;

}

- Can change the output format via use of the

std::dec, std::oct, and std::hexI/O manipulators: - We can define a

std::bitsetvariable and tellstd::bitsethow many bits we want to store.

8.4. Constant expressions & Constexpr variables

Constant expressions: expressions whose values can be fully determined at compile time.- A compile-time constant is a constant whose value is known at compile-time.

- A runtime constant is a constant whose initialization value isn’t known until runtime.

constexpris used to ensure we get a compile-time constant variable where we desire one. Means that the object can be used in a constant expression. The value of the initializer must be known at compile-time. The constexpr object can be evaluated at runtime or compile-time.(immediate constant expression)

Benefits: Compile-time evaluation → reduces runtime overhead by precomputing values. Safer code → ensures that certain values (like array sizes, template parameters) are truly constant. Optimizations → allows the compiler to inline and optimize more aggressively. Expressiveness → lets you write functions and objects that can be used in both compile-time and runtime contexts.

constcan be fully determined at runtime\compile time.

#include <iostream>

// The return value of a non-constexpr function is not constexpr

int five()

{

return 5;

}

int main()

{

constexpr double gravity { 9.8 }; // ok: 9.8 is a constant expression

constexpr int sum { 4 + 5 }; // ok: 4 + 5 is a constant expression

constexpr int something { sum }; // ok: sum is a constant expression

std::cout << "Enter your age: ";

int age{};

std::cin >> age;

constexpr int myAge { age }; // compile error: age is not a constant expression

constexpr int f { five() }; // compile error: return value of five() is not constexpr

return 0;

}

8.6. Constexpr functions

-

constexprfunction is a function that is allowed to be called in a constant expression. -

guaranteed to be evaluated at compile-time when used in a context that requires a constant expression.

-

may be evaluated at compile-time (if eligible) or runtime in a other contexts.

-

are implicitly inline, and the compiler must see the full definition of the constexpr function to call it at compile-time.

-

constevalfunction is a function that must evaluate at compile-time. Consteval functions otherwise follow the same rules as constexpr functions. -

e.g.

#include <iostream>

#include <array>

// constexpr function: can be evaluated at compile-time *or* runtime

constexpr int square(int x) {

return x * x;

}

// consteval function: must be evaluated at compile-time

consteval int cube(int x) {

return x * x * x;

}

int main() {

// --- Compile-time evaluation ---

constexpr int a = square(5); // evaluated at compile-time

constexpr int b = cube(3); // must be compile-time

// --- Runtime evaluation ---

int n;

std::cin >> n; // input at runtime

int c = square(n); // evaluated at runtime (since n is not constant)

// int d = cube(n); // ERROR: consteval requires compile-time argument

std::cout << "square(5) = " << a << "\n";

std::cout << "cube(3) = " << b << "\n";

std::cout << "square(n) = " << c << "\n";

return 0;

}

9. std::string

- The easiest way to work with strings and string objects in C++ is via the

std::string/<string>

9.1. std::cout « , std::cin » , std::getLine(std::cin » std::ws, std::string string)

std::wstellsstd::cinto ignore leading whitespace(tab/enter/newline(s)) before extraction.std::string::lengthreturns length of a string that does not included the null terminator character.ssuffix is astd::stringliterally, no suffix is a C-style string literally. e.g.std::cout << "goo\n"s

Initializing and copy a

std::stringis slow. That’s inefficient

9.2. std::string_view (C++17)

-

std::string_view provides read-only access to an existing string (a C-style string literal, a std::string, or a char array) without making a copy.

-

A std::string_view that is viewing a string that has been destroyed is sometimes called a dangling view. When a std::string is modified, all views into that std::string are invalidated, meaning those views are now invalid. Using an invalidated view (other than to revalidate it) will produce undefined behavior.

-

svsuffix is astd::string_viewliterally -

Modify a std::string is likely to invalidate all std::string_view that view into that.

-

It may or may not be null-terminated.

10. Operators & Bit Manipulation

10.1. Operators

- ez , refer : https://www.learncpp.com/cpp-tutorial/operator-precedence-and-associativity/

Increment/decrement:++x: increment x, then return xx++: copy x, then increment x, return the copy

Comma:(x, y): Evaluate x then y, returns value of y- avoid use this

10.2. bit manipulation.

- To define a set of bit flags, use

uint8/16/32… orstd::bitset - Refers: https://www.learncpp.com/cpp-tutorial/bit-flags-and-bit-manipulation-via-stdbitset/

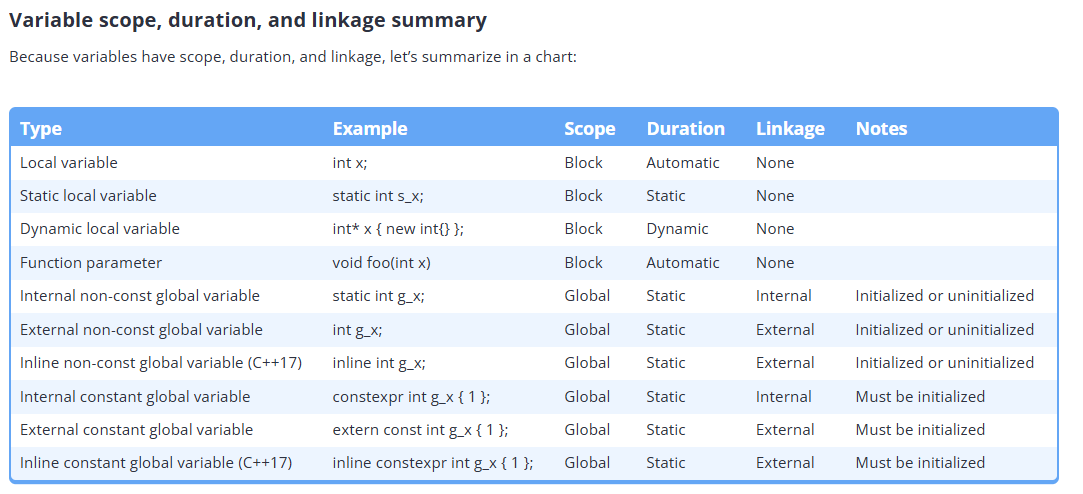

11. Scope, duration, and linkage summary

A variable’s duration determines when it is created and destroyed. Variables with automatic duration: are created at the point of definition, and destroyed when the block they are part of is exited. This includes: - Local variables - Function parameters Variables with static duration: are created when the program begins and destroyed when the program ends. This includes: - Global variables - Static local variables Variables with dynamic duration: are created and destroyed by programmer request. This includes: - Dynamically allocated variables

extern static (or thread_local) storage duration and external linkage static static (or thread_local) storage duration and internal linkage thread_local thread storage duration mutable object allowed to be modified even if containing class is const auto automatic storage duration Deprecated in C++11 register automatic storage duration and hint to the compiler to place in a register Deprecated in C++17

- When you write an implementation file (.cpp, .cxx, etc) your compiler generates a translation unit. This is the source file from your implementation plus all the headers you #included in it. Internal linkage refers to everything only in scope of a translation unit. External linkage refers to things that exist beyond a particular translation unit. In other words, accessible through the whole program, which is the combination of all translation units (or object files).

11.1. Internal linkage

-

An identifier’s linkage determines whether a declaration of that same identifier in a different scope refers to the same entity (object, function, reference, etc…) or not.

-

An identifier with no linkage means another declaration of the same identifier refers to a unique entity. Entities whose identifiers have no linkage include: Local variables Program-defined type identifiers (such as enums and classes) declared inside a block

-

An identifier with

internal linkagemeans a declaration of the same identifier within the same translation unit refers to the same object or function. Entities whose identifiers have internal linkage include:- Static global variables (initialized or uninitialized)

- Static functions

- Const global variables

- Unnamed namespaces and anything defined within them

-

To make things to internal linkage, we can:

staticglobal variables/functionsconstandconstexprglobals ((and thus don’t need the static keyword – if it is used, it will be ignored)) ## C- unnamed namespace { … } (modern C++)

-

static<global_variable>: make the global variable to internal linkage -

static<local_variable>: changes its duration from automatic duration to static duration. And its initializer is only executed once. -

static<const/constexpr local_varialbe>: used to avoid expensive local object initialization each time a function is called because it inits once time. -

Internal linkage for const global variables can change to external with the keyword

extern. e.g.extern const PI = 3.14; -

e.g.

// a.cpp ============================================================

#include <iostream>

static int g_internal { 42 }; // internal linkage (only in a.cpp)

static void helper() { // internal function

std::cout << "Helper in a.cpp\n";

}

int main() {

std::cout << g_internal << '\n'; // OK

helper(); // OK

return 0;

}

// main.cpp ============================================================

extern int g_internal; // ERROR: g_internal not visible outside a.cpp

void helper(); // ERROR: helper not visible outside a.cpp

int main() {

// g_internal; // linker error if uncommented

// helper(); // linker error if uncommented

return 0;

}

11.2. External linkage

-

An identifier with

external linkagemeans a declaration of the same identifier within the entire program refers to the same object or function. Entities whose identifiers have external linkage include:- Non-static functions

- Non-const global variables (initialized or uninitialized)

- Extern const global variables

- Inline const global variables

- Namespaces

-

functions: default external linkage -

global variables:non-const globals: external by default.const/constexpr globals: internal by default

-

To access an external global variable from another file, use

externwithout initializer (forward declaration). -

e.g.

// a.cpp ============================================================

#include <iostream>

int g_external { 100 }; // external by default

extern const int g_limit { 200 }; // const made external

void sayHello() { // external by default

std::cout << "Hello from a.cpp\n";

}

// main.cpp ============================================================

#include <iostream>

extern int g_external; // forward declaration

extern const int g_limit; // forward declaration > < const int g_limit: definition

void sayHello(); // forward declaration

int main() {

sayHello();

std::cout << g_external << " / " << g_limit << '\n';

return 0;

}

11.3. Inline functions and variables

When a call to min() is encountered, the CPU must store the address of the current instruction it is executing (so it knows where to return to later) along with the values of various CPU registers (so they can be restored upon returning). Then parameters x and y must be instantiated and then initialized. Then the execution path has to jump to the code in the min() function. When the function ends, the program has to jump back to the location of the function call, and the return value has to be copied so it can be output. This has to be done for each function call. All of the extra work that must happen to setup, facilitate, and/or cleanup after some task (in this case, making a function call) is called overhead. #include

int min(int x, int y) { return (x < y) ? x : y; } int main() { std::cout « min(5, 6) « ‘\n’; std::cout « min(3, 2) « ‘\n’; return 0; } For functions that are large and/or perform complex tasks, the overhead of the function call is typically insignificant compared to the amount of time the function takes to run. However, for small functions (such as min() above), the overhead costs can be larger than the time needed to actually execute the function’s code! In cases where a small function is called often, using a function can result in a significant performance penalty over writing the same code in-place. However, inline expansion has its own potential cost: if the body of the function being expanded takes more instructions than the function call being replaced, then each inline expansion will cause the executable to grow larger.

inline-expansion:- is a process where a function call is replaced by the code from the called function’s definition.

- use this to avoid such overhead cost.

- do not use the

inlinekeyword to request inline expansion for your functions, because optimizing compilers.

modernly-inline:- should not implement functions (with external linkage) in header files because it lead to

multiple definitionserror. - so we can use

inline-function, it’s useful for header-only libraries

- should not implement functions (with external linkage) in header files because it lead to

11.4. Sharing global constants

-

global constants as internal variables:

- Advantages:

- Works prior to C++16.

- Can be used in constant expressions in any translation unit that includes them.

- Downsides:

- Changing anything in the header file requires recompiling files including the header.

- Each translation unit including the header gets its own copy of the variable.

- e.g.

// constants.h:============================================================

#ifndef CONSTANTS_H

#define CONSTANTS_H

// Define your own namespace to hold constants

namespace constants

{

// Global constants have internal linkage by default

constexpr double pi { 3.14159 };

constexpr double avogadro { 6.0221413e23 };

constexpr double myGravity { 9.2 }; // m/s^2 -- gravity is light on this planet

// ... other related constants

}

#endif

// main.cpp::============================================================

#include "constants.h" // include a copy of each constant in this file

#include <iostream>

int main()

{

std::cout << "Enter a radius: ";

double radius{};

std::cin >> radius;

std::cout << "The circumference is: " << 2 * radius * constants::pi << '\n';

return 0;

}

-

global constants as external variables:

- Advantages:

- Works prior to C++16.

- Only one copy of each variable is required.

- Only requires recompilation of one file if the value of a constant changes.

- Downsides:

- Forward declarations and variable definitions are in separate files, and must be kept in sync.

- Variables not usable in constant expressions outside of the file in which they are defined.

- e.g.

// constants.h:============================================================

#ifndef CONSTANTS_H

#define CONSTANTS_H

namespace constants

{

// Since the actual variables are inside a namespace, the forward declarations need to be inside a namespace as well

// We can't forward declare variables as constexpr, but we can forward declare them as (runtime) const

extern const double pi;

extern const double avogadro;

extern const double myGravity;

}

#endif

// constants.cpp:============================================================

#include "constants.h"

namespace constants

{

// We use extern to ensure these have external linkage

extern constexpr double pi { 3.14159 };

extern constexpr double avogadro { 6.0221413e23 };

extern constexpr double myGravity { 9.2 }; // m/s^2 -- gravity is light on this planet

}

// main.cpp::============================================================

#include "constants.h" // include all the forward declarations

#include <iostream>

int main()

{

std::cout << "Enter a radius: ";

double radius{};

std::cin >> radius;

std::cout << "The circumference is: " << 2 * radius * constants::pi << '\n';

return 0;

}

-

global constants as inline variables:

- If you need global constants and your compiler is C++17 capable, prefer defining inline constexpr global variables in a header file.

- Advantages:

- Can be used in constant expressions in any translation unit that includes them.

- Only one copy of each variable is required.

- Downsides:

- Only works in C++17 onward.

- Changing anything in the header file requires recompiling files including the header.

- e.g.

// constants.h:============================================================

#ifndef CONSTANTS_H

#define CONSTANTS_H

// define your own namespace to hold constants

namespace constants

{

inline constexpr double pi { 3.14159 }; // note: now inline constexpr

inline constexpr double avogadro { 6.0221413e23 };

inline constexpr double myGravity { 9.2 }; // m/s^2 -- gravity is light on this planet

// ... other related constants

}

#endif

// main.cpp::============================================================

#include "constants.h"

#include <iostream>

int main()

{

std::cout << "Enter a radius: ";

double radius{};

std::cin >> radius;

std::cout << "The circumference is: " << 2 * radius * constants::pi << '\n';

return 0;

}

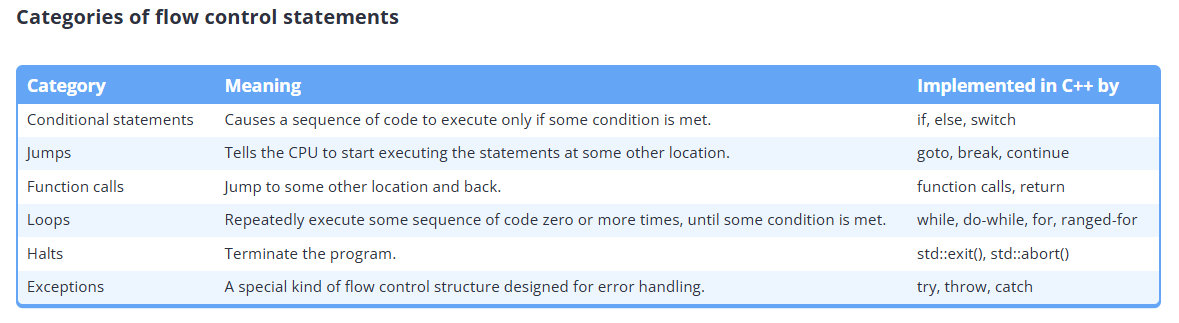

12. Control Flow

12.1. Constexpr if statement

- C++17, that requires the conditional to be a constant expression. It means the condition will be evaluated at runtime.

- Favor constexpr if statements over non-constexpr if statements when the conditional is a constant expression.

- e.g.

#include <iostream>

int main()

{

constexpr double gravity{ 9.8 };

if constexpr (gravity == 9.8) // now using constexpr if

std::cout << "Gravity is normal.\n";

else

std::cout << "We are not on Earth.\n";

return 0;

}

12.2. Switch fallthrough and scoping

- The

[[fallthrough]]attribute modifies a null statement to indicate that fallthrough is intentional (and no warnings should be triggered). - Initialization is not allowed before case labels because control flow in a switch may jump over the initializer, leaving the variable uninitialized.

- Declarations without an initializer are allowed before case labels because they only reserve space for the variable in the function’s stack frame (decided at compile time). No runtime initialization code is generated, so nothing can be “skipped” by jumping to a case.

- e.g.

#include <iostream>

int main() {

int x = 2;

switch (x) {

int a; // allowed (no initializer, just reserves space)

// int b{5}; // not allowed (initializer may be skipped)

case 1:

a = 10; // safe: 'a' exists, we assign here

std::cout << "Case 1, a = " << a << '\n';

[[fallthrough]]; // intentional fallthrough to case 2

case 2:

a = 20; // reassign

std::cout << "Case 2, a = " << a << '\n';

break;

default:

std::cout << "Default case\n";

break;

}

return 0;

}

12.3. Halts

- Halts allow us to terminate our program.Only use a halt if there is no safe or reasonable way to return normally from the main function. If you haven’t disabled exceptions, prefer using exceptions for handling errors safely.

std::exitis called implicitly when main() returns, it does not clean up local variables in the current function or up the call stack.std::abort()function causes your program to terminate abnormally. Abnormal termination means the program had some kind of unusual runtime error and the program couldn’t continue to run.std::terminate()function is typically used in conjunction with exceptions . By default, it callsstd::abort()- e.g.

#include <iostream>

#include <cstdlib> // for std::exit, std::abort

#include <exception> // for std::terminate

void cleanup() {

std::cout << "Cleaning up...\n";

}

void riskyFunction(bool fatalError) {

if (fatalError) {

std::cout << "Fatal error occurred!\n";

// std::abort: abnormal termination, no cleanup

std::abort();

// Or: std::terminate(); // usually called when exception handling fails

}

}

int main() {

cleanup(); // local function call

// Example 1: return normally from main

std::cout << "Program running normally...\n";

// Example 2: using std::exit (implicit when main returns)

if (false) {

std::cout << "Exiting via std::exit...\n";

std::exit(0); // does not call destructors of locals in main()

}

// Example 3: risky code that might abort/terminate

riskyFunction(true);

// Example 4: normal end of main calls std::exit implicitly

std::cout << "Main returns normally.\n";

return 0; // std::exit(0) is called implicitly here

}

13. Error Detection and Handling

14. Type Conversion, Type Aliases, and Type Deduction

Type conversions

│

├── Implicit conversions (compiler tự làm)

│ ├── Numeric promotions ← an toàn, không mất dữ liệu

│ │ ├── char → int

│ │ └── float → double

│ │

│ └── Numeric conversions ← có thể mất dữ liệu

│ ├── Widening conversions ← mở rộng, thường an toàn (int → double)

│ └── Narrowing conversions ← thu hẹp, có thể mất dữ liệu (double → int, int → char)

│

└── Explicit conversions (do lập trình viên ép kiểu)

├── static_cast<int>(3.14)

├── reinterpret_cast

├── const_cast

└── (int)3.14 // C-style cast

14.1. Implicit type conversion

- Implicit type conversion is performed automatically by the compiler when an expression of some type is supplied in a context where some other type is expected.

- numeric promotion is the conversion of certain smaller numeric types to certain larger numeric types (typically int or double).no data loss.

floating point promotion: a value of type float can be converted to a value of type double.integral promotions:- signed char or signed short can be converted to int.

- unsigned char, char8_t, and unsigned short can be converted to int if int can hold the entire range of the type, or unsigned int otherwise.

- If char is signed by default, it follows the signed char conversion rules above. If it is unsigned by default, it follows the unsigned char conversion rules above.

- bool can be converted to int, with false becoming 0 and true becoming 1.

- numeric conversion is a type conversion between fundamental types that isn’t a numeric promotion. A narrowing conversion is a numeric conversion that may result in the loss of value or precision.

14.2. Explicit type conversion

- C++ supports 5 different types of casts:

static_cast,dynamic_cast,const_cast,reinterpret_cast, andC-stylecasts -

C-stylecasts

- Using operator

(<type>)value. and the value to convert to placed immediately to the right of the closing parenthesis). e.g.(int)7/3

-

static_castcasts

- Using `static_cast

(value) - provides compile-time type checking

- less powerful than a C-style cast

- direct-initialized vs list-initialization

| Purpose | Example | Explaination |

|---|---|---|

| Cast object → object | static_cast |

Creates a new Base object copied from Derived (object slicing). |

| Cast object → reference | static_cast<Base&>(derived) | No copy — just changes the view of the same object to treat it as a Base. |

| Cast pointer → pointer | static_cast<Base*>(&derived) | Upcasts a Derived* pointer to a Base* pointer. |

14.3. Typedefs and type aliases

type aliases: use theusingkeyworldusing <NewtypeAlias> = <type>

typedefs: is an old way of creating an alias for a type. Usingtypedefkeyworld.typedef <type> <NewtypeAlias>

- Prefer

type aliasovertypedef

using MyDouble = double;

typedef double MyDouble;

typedef int (*FcnType)(double, char); // FcnType hard to find

using FcnType = int(*)(double, char); // FcnType easier to find

14.5. Type deduction using auto keyworld

- Type deduction allows the compiler to deduce the type of an object from the object’s initializer.

- using

autokeyworld. - Type deduction must have something to deduce from

- Type deduction drops const from the deduced type

- … (more)

- Use type deduction for your variables when the type of the object doesn’t matter.

- Auto can also be used as a function return type to have the compiler infer the function’s return type from the function’s return statements, though this should be avoided for normal functions.

- The auto keyword can also be used to declare functions using a trailing return syntax, where the return type is specified after the rest of the function prototype.

- e.g.

int add(int x, int y)

{

return (x + y);

}

// Using the trailing return syntax, this could be equivalently written as:

auto add(int x, int y) -> int

{

return (x + y);

}

#include <type_traits> // for std::common_type

std::common_type_t<int, double> compare(int, double); // harder to read (where is the name of the function in this mess?)

auto compare(int, double) -> std::common_type_t<int, double>; // easier to read (we don't have to read the return type unless we care)

15. Function Overloading and Function Templates

15.1. Function overloading

function overloadingallows us to create multiple functions with the same name, so long as each identically named function has different parameter types/numbers. Return types are not considered forfunction deleteusingdeletekeywork. delete means “I forbid this”, not “this doesn’t exist”.- e.g.

#include <iostream>

// This function will take precedence for arguments of type int

void printInt(int x)

{

std::cout << x << '\n';

}

// This function template will take precedence for arguments of other types

// Since this function template is deleted, calls to it will halt compilation

template <typename T>

void printInt(T x) = delete;

int main()

{

printInt(97); // okay

printInt('a'); // compile error

printInt(true); // compile error

return 0;

}

default-arguments: is a default value provided for a function parameter. Parameters with default arguments must always be the rightmost parameters, and they are not used to differentiate functions when resolving overloaded functions.

15.2. Function Templates

- The template system was designed to simplify the process of creating functions (or classes) that are able to work with different data types (that are compiled and executed).

template typesare sometimes called generic types, and programming using templates is sometimes called generic programming.placeholder typesuse for any parameter types, return types, or types used in the function body that we want to be specified later, by the user of the template.template parameter declarationdefines any template parameters that will be subsequently used.function templatesallow us to create a function-like definition that serves as a pattern for creating related functions. In a function template, we use type template parameters as placeholders for any types we want to be specified later. The syntax that tells the compiler we’re defining a template and declares the template types is called a template parameter declaration.- Using function templates in multiple files. should be defined in a header file, and then #included wherever needed.

template argument deductionto have the compiler deduce the actual type that should be used from the argument types in the function call.- e.g.

template <typename T> // this is the template parameter declaration defining T as a type template parameter , `typename` or `class` can be used

T max(T x, T y) // this is the function template definition for max<T>

{

return (x < y) ? y : x;

}

template<>

int max<int>(int x, int y) // the generated function max<int>(int, int)

{

return (x < y) ? y : x;

}

template<>

double max<double>(double x, double y) // the generated function max<double>(double, double)

{

return (x < y) ? y : x;

}

int main()

{

std::cout << max<int>(1, 2) << '\n'; // calls max<int>(int, int)

std::cout << max<>(1, 2) << '\n'; // deduces max<int>(int, int) (non-template functions not considered)

std::cout << max(1, 2) << '\n'; // calls max(int, int)

return 0;

}

function templates with multiple templatetypes example:

#include <iostream>

template <typename T, typename U>

auto max(T x, U y) // ask compiler can figure out what the relevant return type is

{

return (x < y) ? y : x;

}

int main()

{

std::cout << max(2, 3.5) << '\n';

return 0;

}

non-type template parameteris a template parameter with a fixed type that serves as a placeholder for a constexpr value passed in as a template argument.

#include <iostream>

template <int N> // int non-type template parameter

void print()

{

std::cout << N << '\n';

}

int main()

{

print<5>(); // no conversion necessary

print<'c'>(); // 'c' converted to type int, prints 99

return 0;

}

16. Compound Types: References and Pointers

| Type | Meaning | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental | A basic type built into the core C++ language | int, std::nullptr_t |

| Compound | A type defined in terms of other types | int&, double*, std::string, Fraction |

| User-defined | A class type or enumerated type (Includes those defined in the standard library or implementation) (In casual use, typically used to mean program-defined types) |

std::string, Fraction |

| Program-defined | A class type or enumerated type (Excludes those defined in standard library or implementation) |

— |

Compound data types(also called composite data type) are data types that can be constructed from fundamental data types (or other compound data types).

16.1. lvalues and rvalues

lvaluesis an expression that evaluates to an identifiable object or function (or bit-field). Can be accessed via an identifier, reference, or pointer, and typically have a lifetime longer than a singleexpressionorstatement.rvaluesis an expression that evaluate to a value. Only exist within the scope of the expression in which they are used.lvaluescan be used anywhere anrvalueis expected.- An assignment operation requires its

leftoperand to be a modifiablelvalueexpression. And itsrightoperand to be arvalueexpression.

16.2. References

-

references is an alias for an existing object/function.

referenceitself is like aconst pointer- Declared as

<type>& reference_name - Any operation on the reference is applied to the object being referenced.

- All references must be initialized.

- Cannot be reseated.

- They aren’t objects

- Can only accept modifiable lvalue arguments (const or non-const)

- Declared as

-

pass-by-reference allows us:

- to pass arguments to a function without making copies of those arguments each time the function is called. (class types)

- to change the value of an argument

-

pass-by-const-reference guaranteeing that the function can not change the value being referenced.

-

lvalue-reference just a reference for an existing lvalue.

-

lvalue-reference-types determines what type of object it can reference by using a single ampersand

<type>&. -

lvalue-reference-variable is a variable that acts as a reference to an lvalue.

-

lvalue-reference-to-const can bind with const or non-const objects.

const <type>& name

The const applies to what is immediately to its left, unless there’s nothing to its left, in which case it applies to what’s on the right.

- E.g.

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

// ---------------------------

// Example of references

// ---------------------------

void increment(int& x) { // pass-by-reference (modifiable lvalue reference)

x += 1; // changes original argument

}

void printConstRef(const std::string& s) { // pass-by-const-reference

// s cannot be modified here

std::cout << "Const-ref: " << s << "\n";

}

int main() {

int a = 10;

// ---- Reference basics ----

int& ref = a; // reference must be initialized

ref = 20; // modifies 'a', since ref is just an alias

std::cout << "a = " << a << "\n"; // prints 20

// Cannot reseat: once 'ref' is bound to 'a', it cannot be bound to another variable

int b = 30;

// ref = &b; invalid, would assign value instead of rebinding

// ---- Pass by reference ----

increment(a); // modifies original 'a'

std::cout << "a after increment = " << a << "\n"; // prints 21

// ---- Pass by const reference ----

std::string text = "Hello";

printConstRef(text); // avoids making a copy

// ---- Lvalue reference variable ----

int& lref = a; // lref is an lvalue-reference-variable to 'a'

lref += 5; // modifies 'a'

std::cout << "a after lref += 5: " << a << "\n";

// ---- Lvalue reference to const ----

const int x = 100;

const int& cref1 = x; // bind to const object

const int& cref2 = a; // also works with non-const object

std::cout << "cref1 = " << cref1 << ", cref2 = " << cref2 << "\n";

// ---- They aren't objects ----

// sizeof(ref) == sizeof(a), because ref is just an alias

std::cout << "sizeof(a) == sizeof(ref): "

<< (sizeof(a) == sizeof(ref)) << "\n";

return 0;

}

16.3. Pointer

-

address-of-operator (&

) returns the memory address of its operand, but not as an address literal. Instead, it returns a pointer to the operand. This pointer holds the address value, and when passed to cout, the stream simply prints that value. -

dereference-operator (*) returns the value at a given memory address as an lvalue, used to access the object being pointed at.

-

pointer is an object that holds a memory address as its value:

- declared as

<type>* ptr_name - This allows us to store the address of some other object to use later.

- we should init the pointers.

- the size of pointer is allways the same (32 or 64-bit architecture)

- can assign an invalid pointer a new value, such as

nullptr wild pointer: pointer that has not been initialized is sometimes called a .dangling pointer: pointer that is holding the address of an object that is no longer valid

- declared as

-

pointer-type is a type that specifies a pointer (like reference-type) by using an asterisk

(<type>*).The type of the pointer has to match the type of the object being pointed at. -

null-pointer (its type is

std::nullptr_t) means something has no value. It often associated with memory address 0. -

pointer-to-const: that points to a value that cannot be modified through the pointer, but the pointer itself is not const.

- declared as

const <type> ptr_name*. - cannot change the value being pointed to, but can make the pointer point to a different address.

- may also point to non-const variables.

- declared as

-

const-pointer: whose stored address cannot be changed after initialization, but the value at that address can be modified.

- declared as

<type>* const ptr_name. - fixed to one address, but we can change the value at that address.

- declared as

-

const-pointer-to-const: cannot be reseated (address fixed) and cannot modify the value it points to.

- declared as

const <type>* const ptr_name. - can only be dereferenced to read the value.

- declared as

pointer-to-pointer void allocateArray(int** ptr, int size) { ptr = new int[size]; // allocate memory and update the original pointer } int myArray = nullptr; allocateArray(&myArray, 5); myArray[0] = 10; // works delete[] myArray;

- e.g.

#include <iostream>

#include <cstdint> // for uintptr_t

int main() {

int x = 42;

// address-of operator (&) returns a pointer to x (not an address literal)

int* ptr = &x;

// Printing the pointer: cout prints the stored address value

std::cout << "Address of x (&x): " << &x << "\n";

std::cout << "Value stored in pointer (ptr): " << ptr << "\n";

// dereference operator (*) gives access to the value at the stored address

std::cout << "Value of x via *ptr: " << *ptr << "\n";

// a pointer is an object that holds a memory address

// we can change its value

ptr = nullptr;

std::cout << "Pointer reset to nullptr: " << ptr << "\n";

// pointer type is declared with '*'

double d = 3.14;

double* pd = &d; // type matches: double* for double

// uintptr_t lets us see the raw numeric value of the address

std::cout << "Numeric address of d: " << (uintptr_t)pd << "\n";

std::cout << "Value of d via *pd: " << *pd << "\n";

// NullPTR =======

int* myNullPtr {}; // value-initialized to nullptr

int* myNullPtr2 {nullptr}; // explicitly initialized to nullptr

// Old C-style (still works, but less safe in C++):

// int* myNullPtr3 {NULL}; // requires <cstddef>

// Const ptr =======

int a = 10;

int b = 20;

// 1. pointer-to-const (const int*)

const int* p1 = &a; // can point to non-const variable

// *p1 = 15; // error: cannot modify value through p1

p1 = &b; // can point to another address

std::cout << "p1 points to: " << *p1 << '\n';

// 2. const-pointer (int* const)

int* const p2 = &a; // must be initialized, fixed address

*p2 = 30; // can modify the value at that address

// p2 = &b; // error: cannot change stored address

std::cout << "p2 points to: " << *p2 << '\n';

// 3. const-pointer-to-const (const int* const)

const int* const p3 = &b; // fixed address + read-only value

// *p3 = 40; // error: cannot modify value

// p3 = &a; // error: cannot reseat pointer

std::cout << "p3 points to: " << *p3 << '\n';

return 0;

}

- pointer-to-pointers:

- a pointer that holds the address of another pointer.

- Using two asterisks to declare a pointer to pointer.

- e.g.

int** ptrptr; - Usages:

- Dynamically allocate an array of pointers

- e.g.

int** array { new int*[10] }; // allocate an array of 10 int pointers - Two-dimensional dynamically allocated arrays

- e.g.

int x { 7 }; // non-constant int (*array)[5] { new int[x][5] }; // rightmost dimension must be constexpr

- void-pointers: Also known as the generic pointer, is a special type of pointer that can be pointed at objects of any data type

- Dereferencing a void pointer is illegal. Instead, the void pointer must first be cast to another pointer type before the dereference can be performed.

- We do not know what type of object it is pointing to, deleting a void pointer will result in undefined behavior.

- function-pointers:

-

e.g.

// fcnPtr is a pointer to a function that takes no arguments and returns an integer int (*fcnPtr)(); -

Assigning a function to a function pointer: just like a normal pointer, and the type (parameters and return type) of the function pointer must match the type of the function.

-

e.g.

// function prototypes int foo(); double goo(); int hoo(int x); // function pointer initializers int (*fcnPtr1)(){ &foo }; // okay int (*fcnPtr2)(){ &goo }; // wrong -- return types don't match! double (*fcnPtr4)(){ &goo }; // okay fcnPtr1 = &hoo; // wrong -- fcnPtr1 has no parameters, but hoo() does int (*fcnPtr3)(int){ &hoo }; // okay -

Calling a function using function pointer: There are two way to do this

- Explicitly derefence

- Implicitly derefence

-

e.g.

int foo(int x) { return x; } int main() { int (*fcnPtr)(int){ &foo }; // Initialize fcnPtr with function foo (*fcnPtr)(5); // call function foo(5) through fcnPtr. int (*fcnPtr2)(int){ &foo }; // Initialize fcnPtr with function foo fcnPtr2(5); // call function foo(5) through fcnPtr2. return 0; } -

Passing functions as arguments to other functions: One of the most useful things to do with function pointers is pass a function as an argument to another function. Functions used as arguments to another function are sometimes called callback functions.

-

16.4. Pass by value/reference/address

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

void printByValue(std::string val) // The function parameter is a copy of str

{

std::cout << val << '\n'; // print the value via the copy

}

void printByReference(const std::string& ref) // The function parameter is a reference that binds to str

{

std::cout << ref << '\n'; // print the value via the reference

}

void printByAddress(const std::string* ptr) // The function parameter is a pointer that holds the address of str

{

std::cout << *ptr << '\n'; // print the value via the dereferenced pointer

}

int main()

{

std::string str{ "Hello, world!" };

printByValue(str); // pass str by value, makes a copy of str

printByReference(str); // pass str by reference, does not make a copy of str

printByAddress(&str); // pass str by address, does not make a copy of str

return 0;

}

- pass-by-address allows us: ~ pass-by-references

- to pass arguments to a function without making copies of those arguments each time the function is called. (class types)

- to change the value of an argument

- #null checking

Pass by reference when you can, pass by address when you must

- !! C++ really passes everything by value

16.5. Return by value/reference/address

-

T returnValue(…): returns a copy (or move) of the object. The caller gets its own value.

-

T& returnReference(…) returns a reference to an existing object. The caller does not own it, so the object must outlive the reference.

-

T * returnAddress(…) returns a pointer (an address) to an object. The caller must handle the pointer carefully (ensure it’s valid and points to a live object).

-

return-by-reference:- avoids making a copy of the object.

- the referenced object must live beyond the scope of the function, otherwise the reference will dangle.

- never return a non-static local variable or temporary by reference.

-

return-by-addressworks almost identically to return-by-reference. -

return-by-valuejust make a copy

Prefer return by reference over return by address unless the ability to return “no object” (using nullptr) is important.

- e.g.

#include <iostream>

int global = 42;

// Return by value: makes a copy

int returnValue() {

int x = 10;

return x; // copy returned

}

// Return by reference: must refer to existing object

int& returnReference() {

return global; // safe: global outlives the function

}

// Return by address: returns a pointer

int* returnAddress(bool valid) {

if (valid)

return &global; // valid pointer

else

return nullptr; // no object

}

int main() {

int a = returnValue();

std::cout << "By value: " << a << '\n';

int& b = returnReference();

std::cout << "By reference: " << b << '\n';

b = 100; // modifies global

std::cout << "Global after modification: " << global << '\n';

int* c = returnAddress(true);

if (c) std::cout << "By address: " << *c << '\n';

int* d = returnAddress(false);

if (!d) std::cout << "By address: got nullptr\n";

}

16.6. In/Out Params

-

in-parameters:are typically passedby valueorby const reference -

out-parameters:a function parameter that is used only for the purpose of returning information back to the caller.- Avoid out-parameters (except in the rare case where no better options exist).

- Prefer pass by reference for non-optional out-parameters.

-

e.g.

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

// In-parameter by value (cheap to copy)

void greet(std::string name) {

std::cout << "Hello, " << name << "!\n";

}

// In-parameter by const reference (avoid copy for large objects)

int length(const std::string& text) {

return text.size();

}

// Out-parameter by reference (rare case)

void square(int input, int& output) {

output = input * input;

}

int main() {

// in-parameter by value

greet("Alice");

// in-parameter by const reference

std::string msg = "Hello World";

std::cout << "Length = " << length(msg) << "\n";

// out-parameter by reference (not preferred, but possible)

int result;

square(5, result);

std::cout << "Square = " << result << "\n";

}

16.7. Type deduction (auto) with pointers, references, and const

https://www.learncpp.com/cpp-tutorial/type-deduction-with-pointers-references-and-const/

16.8. std::optional

https://www.learncpp.com/cpp-tutorial/stdoptional/

18. Compound Types: Enums and Structs

program-defined-typesare types that programmers create themself.

In C++, struct, class, and union automatically create a new type name, so you don’t need to prefix variables with the keywords struct or union as in C.

18.1. Enumerations

enumis a compound types where every possible value is defined as a symbolic constant.- Named starting with a capital letter. Named enumerators starting with a lower case letter.

unscoped-enum: put their enumerator names into the same scope as the enumeration definition itselfscoped-enum: keep their enumerators inside the enum’s own scope.Usingenum classkeyworld.using enum <EnumName>statement imports all the emnumerators from an enum into the current scope.- putting your enumerations inside a named scope region (such as a namespace or class) so the enumerators don’t pollute the global namespace.

- Specify the base type of an enumeration only when necessary.

- e.g.

#include <iostream>

#include <cstdint> // for uint8_t

// Good naming style:

// Enum name: Capitalized

// Enumerator names: lowercase

enum Color {

red,

green,

blue

};

// Scoped enum — enumerators are inside the enum’s scope

enum class Shape {

circle,

square,

triangle

};

// Scoped enum inside a namespace — prevents name pollution

namespace Game {

enum class Direction {

up,

down,

left,

right

};

}

// Scoped enum with explicit base type

enum class Status : uint8_t {

ok = 0,

error = 1,

unknown = 2

};

int main() {

// Using unscoped enum

Color c = red; // direct access (same scope)

std::cout << "Color value: " << c << "\n";

// Using scoped enum

Shape s = Shape::circle; // must use scope name

if (s == Shape::circle)

std::cout << "Shape is circle\n";

// Scoped enum inside namespace

Game::Direction dir = Game::Direction::up;

if (dir == Game::Direction::up)

std::cout << "Direction is up\n";

// Scoped enum with base type

Status st = Status::ok;

if (st == Status::ok)

std::cout << "Status OK (base type uint8_t)\n";

return 0;

}

18.2. Struct

- A struct is a class type (just like

classesorunion), allows us to bundle multiple variables together into a single type. As such, anything that applies to class types applies to structs. - Defining structs using

structkeywords. - Access struct members:

- Use member selection operator(dot operator)

.for reference/object. - Use arrow operator

->for pointers.ptr->id = (*ptr).id

- Use member selection operator(dot operator)

- Initialization:

- using brace-initialization

{}or by defining default member values. - should provide a default value for all members

- Struct aggregate initializations:

- using brace-initialization

Employee frank = { 1, 32, 60000.0 }; // copy-list initialization using braced list

Employee joe { 2, 28, 45000.0 }; // list initialization using braced list (preferred)

-

Passing and returning structs:

- Passingy reference (efficient and avoids copying)

- Passing temporary

- Create a struct variable and return

- Returning a temporary (unnamed/anonymous) object

-

Struct size and data structure alignment:the size of a struct will be at least as large as the size of all the variables it contains. But it could be larger! For performance reasons, the compiler will sometimes add gaps into structures this is called padding. We can minimize padding by defining your members in decreasing order of size.(e.g., double → int → char).

-

e.g.

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

using namespace std;

// Define a struct

struct SensorData {

double voltage{0.0}; // Default initialization

int id{0};

char status{'N'}; // 'N' = normal, 'E' = error

string label{"Unknown"};

// Member function

void print() const { // Const class objects and const member functions

cout << "Sensor " << id

<< " [" << label << "] "

<< "Voltage: " << voltage

<< " Status: " << status << endl;

}

};

// Function that accepts struct by reference

void updateVoltage(SensorData &data, double newV) {

data.voltage = newV;

}

// Function returning a temporary struct

SensorData makeSensor(int id, double v, const string &label) {

return {v, id, 'N', label};

}

int main() {

// Initialization using braces

SensorData s1{3.3, 1, 'N', "Temperature"};

s1.print();

// Pointer access

SensorData *ptr = &s1;

ptr->status = 'E';

ptr->print();

// Passing by reference

updateVoltage(s1, 4.8);

s1.print();

// Returning temporary struct

SensorData s2 = makeSensor(2, 5.0, "Pressure");

s2.print();

cout << "Size of struct = " << sizeof(SensorData) << " bytes" << endl;

return 0;

}

18.3. Class template

- a class template is a template definition for instantiating class types (structs, classes, or unions). Class template argument deduction (CTAD) is a C++17 feature that allows the compiler to deduce the template type arguments from an initializer.

- Using class template in a function:

- e.g.

#include <iostream>

template <typename T>

struct Pair

{

T first{};

T second{};

};

template <typename T>

constexpr T max(Pair<T> p)

{

return (p.first < p.second ? p.second : p.first);

}

int main()

{

Pair<int> p1{ 5, 6 }; // instantiates Pair<int> and creates object p1

std::cout << p1.first << ' ' << p1.second << '\n';

Pair<double> p2{ 1.2, 3.4 }; // instantiates Pair<double> and creates object p2

std::cout << p2.first << ' ' << p2.second << '\n';

Pair<double> p3{ 7.8, 9.0 }; // creates object p3 using prior definition for Pair<double>